What does it mean to “engage your core,” “pull your belly in” or even “hollow body”? We often assume we know what these shorthand phrases mean to our patients/students/instructors, but what do we really want? What are we asking the muscles to do? What are we trying to get students to achieve? A look? A feeling? And how do we know if they get it right?

The most supportive engagement of the core involves muscles on all sides compressing the abdomen. The whole abdominal cavity is surrounded by muscle creating a cylinder of support. At the base of the cylinder is the pelvic floor. The walls are formed by the transversus abdominus, internal and external obliques wrapping around the midsection. At the top of the cylinder is the diaphragm. This system is stable but it isn’t static. The diaphragm needs to be able to contract and relax as it drives respiration.

In the last post we talked about how breathing helps stabilize the trunk. Today let’s talk about what that should look like to an outside observer and what it should feel like to the artist.

For the observer. What does an engaged core LOOK like?

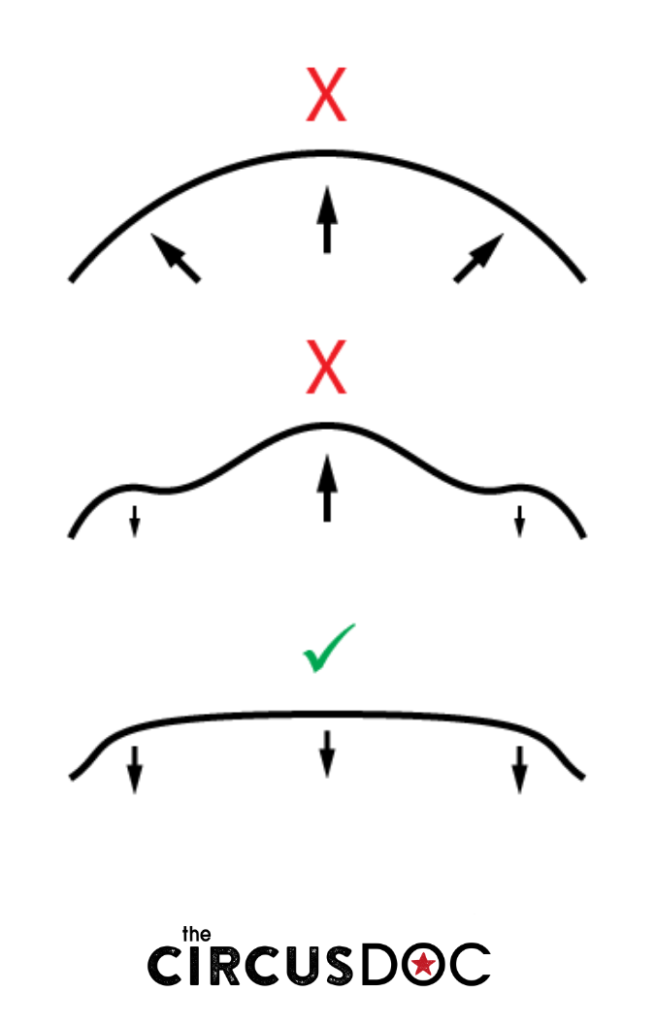

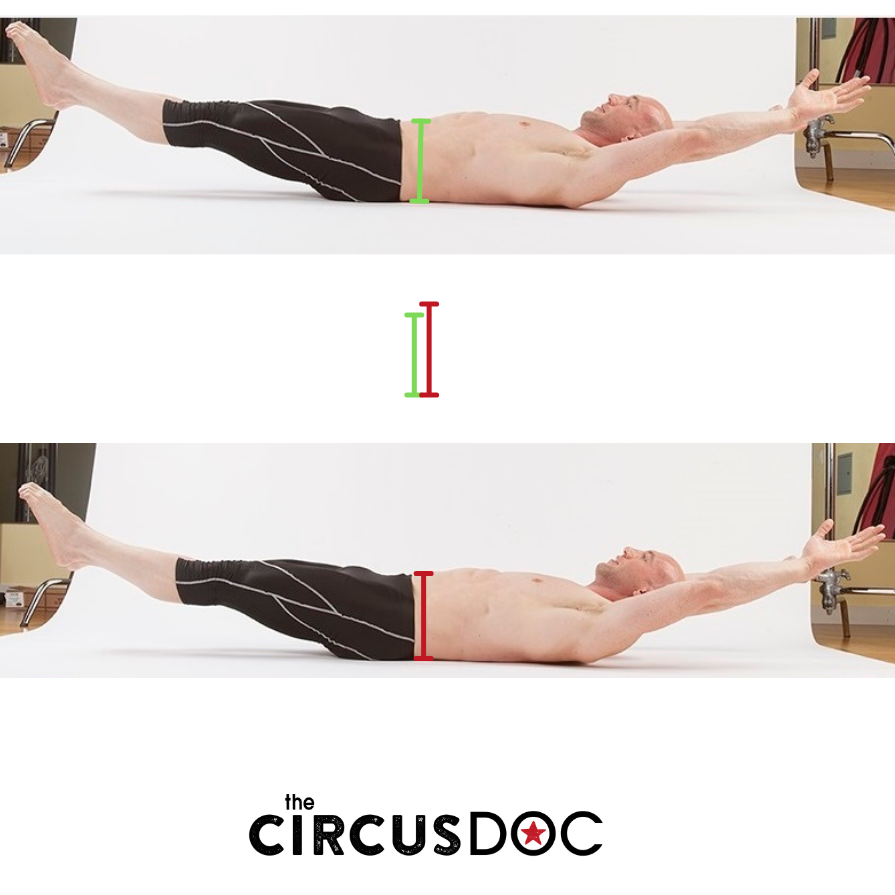

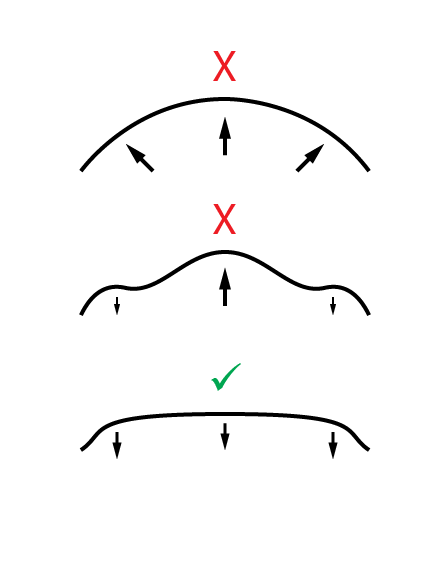

We should see a smooth curve of contraction across the abdominals (as in the illustration). If the whole belly is pressed forward, it can mean the artist is bearing down and stretching the abdominals outwards to create tension. More commonly artists will press the middle of their belly forward with an excessive contraction of the rectus abdominus leaving a concave hollow on either side of the abdomen. The rectus contributes to creating the shape and look of a hollow body position, but it does not add much to the stability of the trunk.

In can be hard to see, but a sharp-eyed clinician or instructor will be able to help a student see this compensation. With improved support, the artist will be able immediately be able to improve their control.

Moving up to look at the ribcage, we should be able to see the artist breathing in and out while maintaining the abdominal contraction. An artist with a great supportive engagement will be able to have flexibility in their diaphragm to continue normal respiration. One way an artist can compensate for a stable abdominal engagement is to hold the ribcage in expansion. This stretches the abdominals and creates a less-functional tension. To spot this, look at the artist’s ribcage: if you see a static expansion with a barrel-chested look, they might be compensating.

Now to the artist’s perspective: What does it FEEL like?

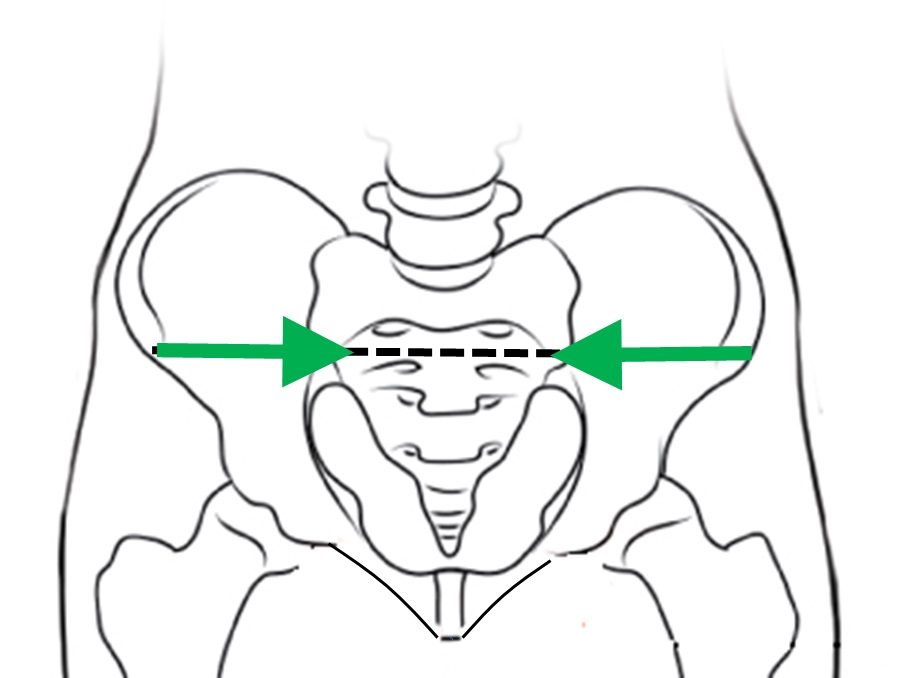

A solid contraction may feel like; a bungee cord between their ASIS (hip bones), the belly button pulling inward towards the spine or trying to zip up pants that are a size too small (without expanding the ribcage).

The muscles just inside the ASIS should feel taught. If none of those cues work, make your patient laugh! It should feel like that contraction! A forceful exhale helps recruit the same abdominal muscles.

Love this article! Thank you sooo much, and very useful diagrams! <3 Great cues too – I shall imagine the bungee cord!