Circus shoulders in the clinic

As a circus physical therapist I work with folks a LOT on their shoulders to help them achieve the mobility and stability needed to balance on or hang from their hands. A novice circus practitioner might not have the strength needed to allow for overhead mobility. An intermediate to advanced artist might be working on skills that involve a lot of pulling that need to be balanced with opposing muscles to maintain or improve their mobility. A professional artist might fall into that category as well, or might have an old injury they have been working around that either needs support to heal or the artist might need guidance to train out of a pattern that had purpose, but now is no longer helping them achieve their goals.

Lack of balanced strength or inefficient movement patterns can hold an artist back from gaining that next skill or having a pain-free class or performance. So, when I see the same limiting movement pattern repeatedly in a short timeframe, especially when it is in folks across a variety of aerial and ground disciplines, that’s when I really feel the need to share what I am finding.

A repeated pattern…

The folks I have been seeing all had pain in their shoulder with their arm overhead (they were in a physical therapy clinic after all) but this pattern can show up and make skills just a bit harder even without pain.

When I looked at their hanging or handstand position that they were having pain in and asked what they were thinking about and/or feeling, all of these folks said they were trying to “wrap their scapula” when they were “engaging their shoulders”…

That all sounds great, right? But, they were having pain! So, what was happening?!? Why were they having trouble?!?

Let’s start at the beginning…

What is scapular wrapping? Is it different than shoulder engagement? And what the heck is an engaged shoulder?!?

Scapular wrapping (scap wrap) is when the scapula tips backwards and glides around the ribcage so that the bottom corner of the shoulder blade comes into the armpit. This position allows the artist to “engage” and support their shoulder girdle in an alignment that makes overhead positioning easier (once they have the strength), more balanced across the musculature, and therefore more stable.

Did you know that the scapula can and should move that much?

If this is a new concept for you, test it out. Put one hand on your rib cage under your opposite side armpit, reach around as far as you are comfortable. Bring your free arm overhead but don’t think too hard about how you’re moving it. Let it do its natural thing… Did you feel your scapula move under your first hand?

What was happening for these folks was a greater emphasis on the “wrap”, the protraction of the scapula on the ribcage, without getting the very important posterior tilt component which brings the inferior (bottom) angle of the scapula forwards and tips the shoulder blade backwards and the joint upwards as it moves around the ribcage. This tilt is the motion that is most important to point the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint upwards and allows for the full range of motion.

So the scap can do both? How does that happen?

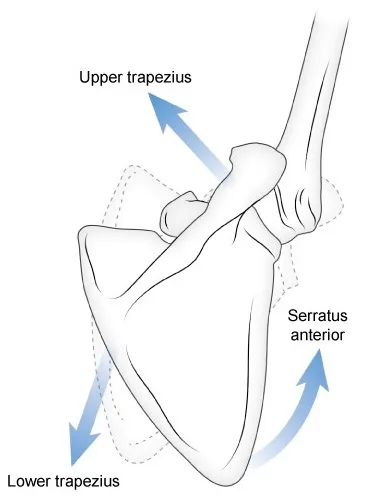

OK, so now you may be asking, how does that happen? Well, both pectoralis muscles and the serratus anterior muscle protract the scapula, but only the serratus anterior tilts it backwards. The pectoralis minor and major will actually tilt the scapula forwards, keeping the glenohumeral joint lower. (Also related to hanging, the pectoralis major also adducts the humerus which can also mimic scapular wrapping (but that’s a story for another time…)

This difference in muscle action changes how the scapula moves and stabilizes. Great, you may think, but why does this matter?

Well, the ball and socket joint at the shoulder, made up of the glenoid and the humerus, is one of the most mobile in the body. So if the shoulder blade isn’t moving well this mobile joint might just take up the slack increasing the pressure on the joint structures including the rotator cuff musculature.

Illustration of scapular motion from Applied Anatomy of Aerial arts by Emily Scherb, DPT copyright 2018 North Atlantic Books

Can you spot the difference?

The arm is overhead but the shoulder has less mobility with more activation at the pec muscles with more protraction of the scapula but less upwards rotation and posterior tilt.

Here the arm is overhead with full shoulder mobility with better upwards rotation and posterior tilt of the scapula due to more serratus anterior activation during the movement

So, what in the world do we do about it?!?

From handstand to hanging the concept and movement pattern of the shoulder is similar. We are looking for the same scapular and humeral position just with one under a compressive force and the other traction. Therefore, our beginning exercises can be similar as we introduce the movement patterns. In fact, some of our aerialists would benefit from learning how this motion works in pushing instead of always pulling… but the next steps of re-training for an aerialist and a ground acrobat will look different as they learn to apply what they are learning to their discipline

Here are two of my favorite exercises for handstanders and long arm hangers!

In this video you can see me demonstrating on the first repetition the over wrapping/ protraction of the scapula.

On the subsequent repetitions I am showing engagement driven by humeral external rotation which encourages rotator cuff stability and uses those muscles, which attach on the scapula, to help guide the scapular positioning as I find the engagement without pulling down or pressing forwards.

In this pushing exercise I am once again demonstrating a more pec and upper trap driven performance of the first repetition with the humerus rotating into internal rotation. On the second repetition look for the shoulder blade to wrap more around the body as my thoracic spine flattens out and I am pushing my hips away.

In each exercise I am emphasizing the positioning and muscular performance the artist will need for their discipline.

With pushing we are talking about creating length in the side body, or pressing their hips away from the wall and towards the back of the room… I try to have at least 3-5 ways to cue any movement to reach the most folks possible

With pulling I am emphasizing the humeral (not forearm) rotation and maintaining the arm by the ear to achieve that scapular posterior tilt.

Give them a try on yourself, your patients, or your students!

Let me know what you think!!!